What is a Motor Unit Composed Of? A Comprehensive Guide to Its Structure and Function

Meta Description: Discover the essential components of a motor unit: an alpha motor neuron and the muscle fibers it innervates. Understand how these elements work together for muscle contraction.

Every time you pick up a pen, lift a weight, or even blink, you’re activating a complex and elegant biological system. At the heart of every single one of these movements, from the most delicate to the most powerful, is the motor unit. Understanding this fundamental building block is the key to unlocking how our nervous system translates thought into action. But what is a motor unit composed of, and how do its parts work in such perfect harmony?

If you’re an engineer, a student of physiology, or anyone fascinated by the mechanics of the human body, you’ve come to the right place. This guide will break down the motor unit into its core components, explain how they function together, and explore why this microscopic system is so critical for everything we do.

In This Article

- Defining the Motor Unit: The Building Block of Movement

- The Two Core Anatomical Components

- The Neuromuscular Junction: The Critical Connection Point

- How Motor Unit Components Orchestrate Muscle Contraction

- Types of Motor Units: Functional Classification

- The Bigger Picture: Why Motor Units Matter in Health and Disease

- Conclusion: The Integrated System for Movement

Defining the Motor Unit: The Building Block of Movement

In the simplest terms, a motor unit is the fundamental functional unit of muscle control. Think of it as the smallest operational team in your body’s “movement department.” It’s not just a muscle cell or a nerve cell; it’s the inseparable partnership between the two.

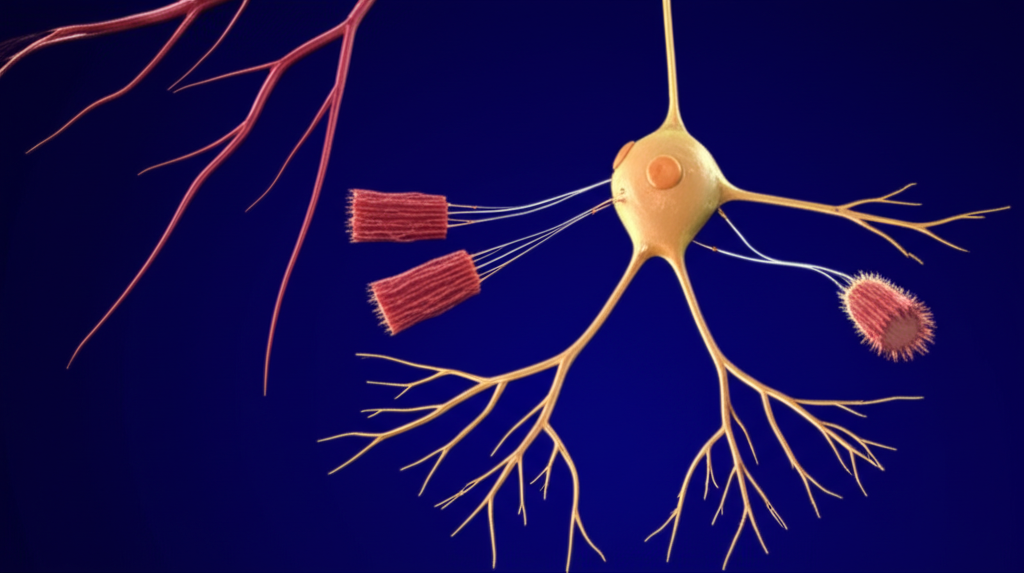

A motor unit consists of two primary components:

Imagine a general (the motor neuron) giving a command. That single command doesn’t just go to one soldier; it goes to an entire platoon (the muscle fibers) that has been assigned to that general. When the general gives the order to “fire,” every single soldier in that platoon fires simultaneously and with full force. This is precisely how a motor unit works. The neuron is the commander, and the muscle fibers are the obedient soldiers that execute the command in unison. This all-or-none principle is central to how we generate and control force.

The Two Core Anatomical Components

Let’s break down the two main players on this team: the neuron that sends the signal and the muscle fibers that do the heavy lifting.

The Conductor: The Alpha Motor Neuron

The alpha motor neuron is the nerve cell that serves as the final common pathway for all commands from the central nervous system (CNS) to the muscle. These are some of the most impressive cells in the body.

- Origin and Structure: The journey begins in the central nervous system. The cell body, or soma, of an alpha motor neuron resides safely within the gray matter of the spinal cord or the brainstem. From this soma, branching structures called dendrites reach out to receive signals from the brain (via upper motor neurons) and other local circuits. The main output cable is a long, slender projection called the axon.

- Axon Path: This axon is the information superhighway. It exits the spinal cord, travels through the peripheral nervous system bundled with other nerves, and heads toward its target muscle. To ensure the signal travels quickly and without losing strength, the axon is wrapped in a fatty insulating sheath called myelin. Thanks to this insulation, these neurons boast remarkable conduction velocities, with nerve impulses traveling at speeds up to 120 meters per second.

- Axon Branching: As the axon approaches its target muscle, it splits into numerous fine branches called axonal collaterals. Each of these tiny branches terminates on a single muscle fiber. This branching is what allows one neuron to control multiple muscle fibers, which can range from just a handful to several thousand.

The Workforce: The Innervated Skeletal Muscle Fibers

The recipients of the motor neuron’s command are the skeletal muscle fibers. These are long, cylindrical cells responsible for generating the force that produces movement.

- Homogeneity: A crucial characteristic of a motor unit is that all muscle fibers innervated by a single motor neuron are of the same type. You won’t find a mix-and-match platoon. If the neuron is a “slow-twitch” commander, it will only control slow-twitch (Type I) muscle fibers. If it’s a “fast-twitch” commander, it will only control fast-twitch (Type II) fibers. This ensures that the unit has a consistent and predictable functional profile—either built for endurance or for power.

- Innervation Ratio: This term describes the number of muscle fibers controlled by a single motor neuron. The ratio varies dramatically throughout the body and is directly related to the muscle’s function.

- Fine Motor Control: In muscles that require exquisite precision, like those controlling eye movement or the fingers, the innervation ratio is very low. A single motor neuron might control only 3-10 muscle fibers. This allows for tiny, incremental adjustments in force.

- Gross Motor Control: In large, powerful muscles like the quadriceps in your thigh or the gastrocnemius in your calf, the innervation ratio is extremely high. One motor neuron can innervate 1,000 to 2,000 muscle fibers. When this neuron fires, it creates a powerful, large-scale contraction. It’s less about precision and all about generating maximum force.

The relationship between neuron and fiber is absolute. If the motor neuron dies or is damaged, the muscle fibers it controls lose their connection and can no longer contract, a condition known as denervation which leads to muscle atrophy.

The Neuromuscular Junction: Where Nerve Meets Muscle

So, how does the electrical command from the neuron actually make the muscle fiber contract? The magic happens at a highly specialized connection point called the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). It’s a microscopic gap, a chemical synapse, where the nerve ending meets the muscle fiber. Think of it as the ultimate biological plug-and-socket connection, converting an electrical signal into a chemical one, and then back into an electrical signal.

The NMJ itself has three key parts:

1. Presynaptic Terminal

This is the very end of the motor neuron’s axon branch. It’s swollen slightly and packed with thousands of tiny sacs called synaptic vesicles. Each of these vesicles is filled with a crucial chemical messenger, a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine (ACh). When the action potential (the electrical signal) arrives at the terminal, it triggers these vesicles to release their ACh content.

2. Synaptic Cleft

This is the minuscule physical gap—only about 20-40 nanometers wide—that separates the nerve ending from the muscle fiber. The nerve doesn’t actually touch the muscle. The released acetylcholine molecules must diffuse across this tiny space to deliver their message.

3. Postsynaptic Membrane (Motor End Plate)

On the muscle fiber side of the synapse is a specialized, folded region of the cell membrane called the motor end plate. This area is densely populated with millions of acetylcholine receptors. When ACh molecules travel across the synaptic cleft, they bind to these receptors, much like a key fitting into a lock. This binding action opens ion channels, allowing positively charged ions (mostly sodium) to rush into the muscle cell. This influx of positive charge creates a new electrical signal called an end-plate potential (EPP), which, if strong enough, triggers a full-blown muscle action potential.

The reliability of this connection is astounding. The NMJ operates with a high safety factor, meaning the neuron typically releases far more acetylcholine than is needed to trigger a contraction. This ensures that every command from the neuron is successfully translated into a muscle response, without fail.

From Signal to Action: How a Motor Unit Creates Contraction

Now let’s put it all together. The entire process, from a thought in your brain to a physical movement, involves a stunningly rapid and precise sequence of events orchestrated by your motor units.

This entire sequence adheres to the all-or-none principle: if the stimulus from the neuron is strong enough to reach the threshold, all the muscle fibers within that specific motor unit will contract completely. There’s no such thing as a partial contraction of a motor unit.

Not All Motor Units Are Created Equal: Functional Classification

Your body doesn’t just have one type of motor unit. To achieve the incredible range of human movement—from holding a delicate object to executing an explosive jump—the nervous system uses different types of motor units with distinct properties. This is where the engineering principles of power, speed, and efficiency come into play.

The recruitment of these units is governed by Henneman’s Size Principle. It states that motor units are recruited in order of their size, from smallest to largest. As you need to generate more force, your brain progressively activates larger and more powerful motor units. This allows for smooth, graded control over muscle force.

Here are the three main types:

- Slow (S) or Type I Motor Units: These are the marathon runners of the muscular world. They consist of a small alpha motor neuron innervating Type I (slow-oxidative) muscle fibers.

- Characteristics: Low force output, slow contraction speed, but incredibly fatigue-resistant. They are rich in mitochondria and myoglobin, using oxygen to produce energy efficiently.

- Function: They are recruited first for almost any activity and are responsible for sustained contractions, such as maintaining posture, walking, and endurance activities.

- Fast Fatigue-Resistant (FR) or Type IIa Motor Units: These are the versatile all-rounders. They involve an intermediate-sized motor neuron connected to Type IIa (fast oxidative-glycolytic) fibers.

- Characteristics: They produce more force and contract faster than S-type units. They have good aerobic capacity but can also function anaerobically, making them moderately resistant to fatigue.

- Function: These are recruited after the S-type units when more force is needed, such as during jogging, cycling, or lifting moderate weights.

- Fast Fatigable (FF) or Type IIb/IIx Motor Units: These are the sprinters. They are the largest motor units, with a large alpha motor neuron innervating Type IIb/IIx (fast glycolytic) fibers.

- Characteristics: They generate the greatest amount of force and have the fastest contraction speed. However, they rely on anaerobic metabolism, which means they run out of fuel quickly and fatigue rapidly.

- Function: These are reserved for short, explosive movements requiring maximum effort, like sprinting, jumping, or lifting a maximal load. They are the last to be recruited and the first to deactivate.

The sophisticated interplay between these unit types is what allows for precise control. Your nervous system isn’t just flipping a switch; it’s acting like a conductor, bringing in different sections of the orchestra as the intensity of the “music” demands. This elegant system ensures that energy isn’t wasted on using powerful, fast-fatiguing units for a task that only requires fine, sustained control. The fundamental motor principle is about efficiency—using only what is necessary for the task at hand.

The Bigger Picture: Why Motor Units Matter in Health and Disease

A clear understanding of what a motor unit is composed of isn’t just academic; it has profound implications for clinical medicine, rehabilitation, and sports science.

- Neurological Disorders: Many devastating diseases target specific components of the motor unit.

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): This disease causes the progressive degeneration and death of both upper and lower motor neurons, including the alpha motor neurons. As the neurons die, the muscle fibers they control are left denervated, leading to muscle weakness, twitching (fasciculations), and eventual atrophy.

- Myasthenia Gravis: This is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s own immune system attacks and destroys the acetylcholine receptors on the motor end plate. This weakens the neuromuscular junction, making it harder for the neuron’s signal to trigger a muscle contraction. The result is fluctuating muscle weakness that worsens with repeated use.

- Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA): A genetic disease that affects the survival of motor neurons in the spinal cord, leading to progressive muscle weakness and atrophy from a very young age.

- Diagnostic Tools: Electromyography (EMG) is a technique used to assess the health of motor units. By inserting fine needles into a muscle, neurologists can record the electrical activity of motor units at rest and during contraction. The size, shape, and firing pattern of the motor unit action potentials can reveal whether a problem originates in the nerve (neuropathy) or the muscle itself (myopathy). Just as an engineer analyzes the performance of motor core laminations to ensure efficiency, a clinician analyzes EMG signals to diagnose neuromuscular health.

- Exercise and Aging: The concept of the motor unit is central to exercise physiology.

- Strength Training: Lifting heavy weights forces the nervous system to recruit more motor units, especially the large, fast-fatigable (FF) type. This training improves the synchronization and firing rate of these units, leading to greater strength gains even before significant muscle hypertrophy (growth) occurs. The muscle fibers themselves become more robust, much like a rotor core lamination is built to withstand immense forces.

- Aging: Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is partly due to a gradual loss of motor units. As motor neurons die off with age, their orphaned muscle fibers may be reinnervated by surviving neurons, forming larger, less efficient motor units. This remodeling process contributes to a loss of fine motor control and overall strength in the elderly.

Conclusion: The Integrated System for Movement

So, what is a motor unit composed of? At its core, it’s a beautifully simple yet powerful partnership: a single alpha motor neuron and the specific group of muscle fibers it commands. This trio of components—the neuron, the muscle fibers, and the neuromuscular junction that connects them—forms the final common pathway for every voluntary movement you make.

From the delicate arrangement of fibers in a small motor unit that allows an artist to paint, to the massive recruitment of thousands of fibers in a large motor unit that lets a weightlifter succeed, these structures are the bedrock of human performance. The organization is remarkably efficient, mirroring principles seen in advanced engineering. The muscle fibers are grouped and activated in unison, much like how a precisely engineered stator core lamination directs magnetic fields to produce smooth, powerful rotation.

By understanding this fundamental relationship between nerve and muscle, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of the human body and a clearer insight into the mechanisms behind strength, skill, disease, and the very essence of movement itself.