Your Body’s Amazing Command Center: A Simple Guide to Motor Function

Have you ever stopped to think about how you can kick a ball, write your name, or even just walk across the room? It seems so easy, but it’s actually an incredible process run by your brain. This is your motor function at work. It’s the system that lets you move and interact with the world. But sometimes, our movements feel clumsy or uncoordinated, and we don’t know why. If you’ve ever felt frustrated trying to learn a new sport or wondered how athletes perform amazing feats, you’re in the right place. We’re going to explore how your body moves, why it sometimes doesn’t, and how it all connects in a way that’s simple and fun to understand.

Table of Contents

- What in the World Is Motor Function?

- How Does Your Brain Send Moving Orders?

- Are You a Gross Motor or Fine Motor Master?

- Who Is the Captain of Your Movement Team?

- What Does the “Little Brain” Do?

- Why Don’t You Fall Over More Often?

- How Do We Learn to Ride a Bike or Play Guitar?

- What Happens When the Wires Get Crossed?

- Can You Actually Improve Your Motor Skills?

- How Is Your Body Like an Electric Motor?

- Frequently Asked Questions About Motor Function

- Key Takeaways to Remember

What in the World Is Motor Function?

Let’s start with the basics. What does “motor function” even mean? Think of it like this: your body is a super advanced machine, and your brain is the command center. Motor function is simply the process of your brain telling your body how to move. It’s everything from the big movements, like running and jumping, to the tiny, precise movements, like wiggling your toes or threading a needle.

You use motor function every single second of the day, usually without even thinking about it. When you wake up and stretch, that’s motor function. When you brush your teeth, that’s motor function. Even the little muscles that help you blink and smile are controlled by this amazing system. It’s so good at its job that we often take it for granted. But when you think about all the coordination it takes to just walk without falling, you realize it’s a pretty big deal.

This system isn’t just one thing; it’s a huge team of players working together. It includes your brain, your spinal cord, all the nerves that branch out to your muscles, and the muscles themselves. They all have to communicate perfectly for you to make a smooth, controlled movement. If there’s a miscommunication anywhere along the line, your movement might be jerky, slow, or just not what you intended. It’s like a game of telephone, and the message needs to be crystal clear from start to finish.

How Does Your Brain Send Moving Orders?

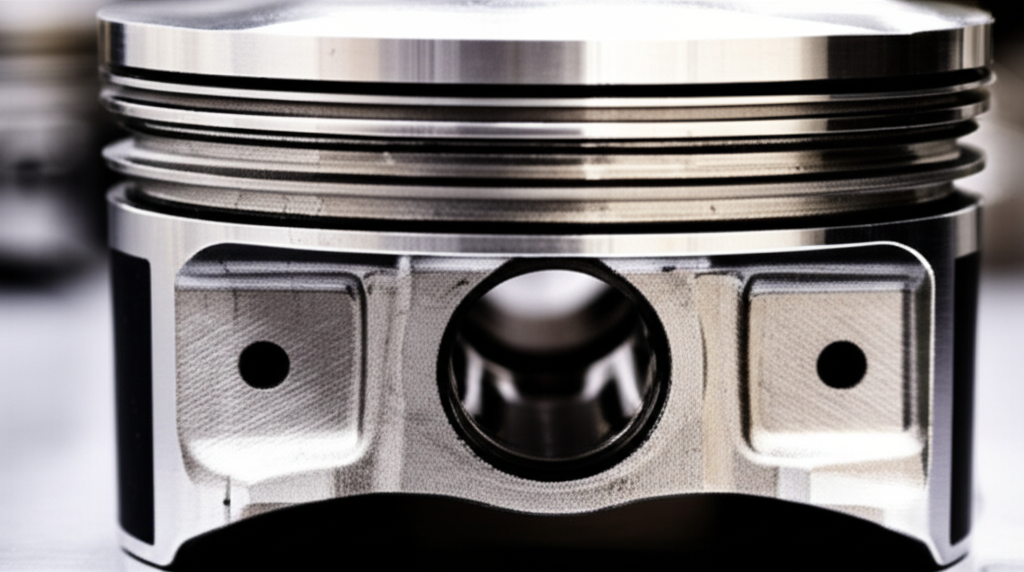

So how does the message get from your brain to your big toe? It all happens through your nervous system, which is like the electrical wiring of your body. Imagine you decide you want to pick up a glass of water. That thought starts in your brain, specifically in an area called the motor cortex. Think of this as the main office where all the big decisions are made.

Once the decision is made, the motor cortex sends an electrical signal. This signal is like a tiny bolt of lightning, and it doesn’t travel alone. It zips down your spinal cord, which is like a superhighway for these messages running down your back. From the spinal cord, the message travels along smaller nerves, which are like side roads that lead directly to the specific muscles you need to use in your arm and hand.

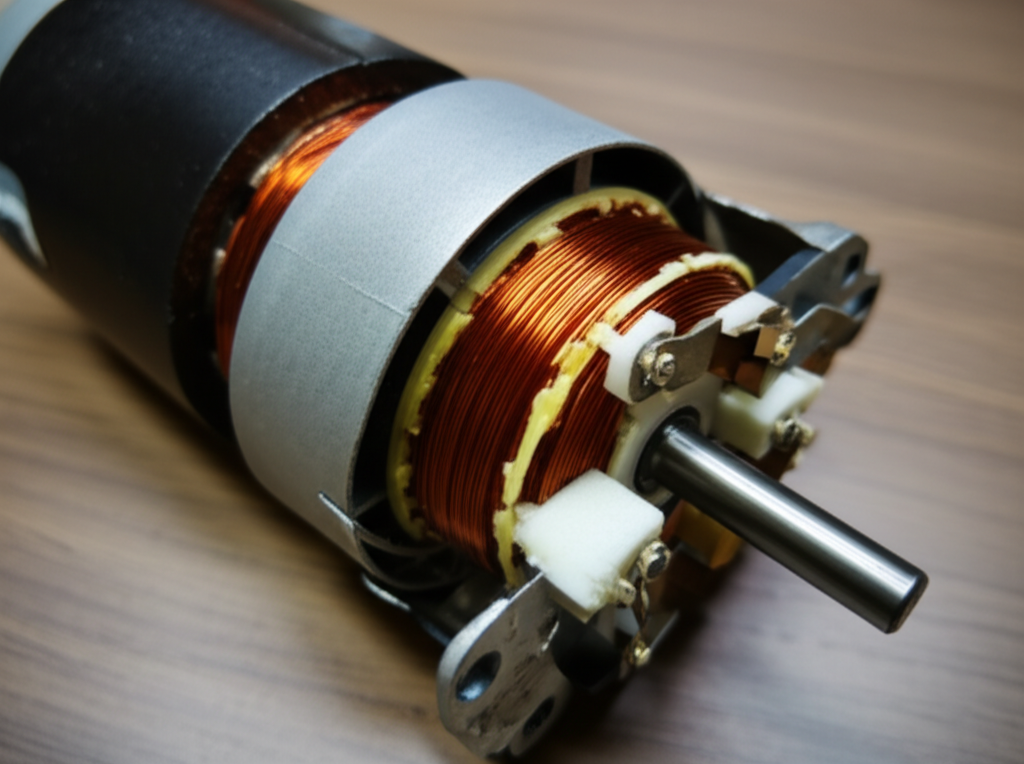

When the signal reaches the muscle, it delivers the order: “Contract!” or “Tighten up!” As the right muscles tighten in the right order, your arm extends, your fingers wrap around the glass, and you lift it. All of this happens in less than a blink of an eye. It’s an incredibly fast and complex process, but your body does it so effortlessly that you don’t even notice. The efficiency of this system is amazing and depends on all parts working together, much like how the performance of an electric motor depends on its core components.

Are You a Gross Motor or Fine Motor Master?

You might have heard people talk about “motor skills,” but did you know there are two main types? They are called gross motor skills and fine motor skills. Understanding the difference is pretty simple once you break it down.

Gross motor skills are all about the big movements. These are the actions that use the large muscles in your arms, legs, and torso. Think about running across a field, jumping over a puddle, or throwing a baseball. These activities require strength and coordination of your whole body. Even just sitting up straight or standing on one foot uses your gross motor skills to keep you balanced and stable. Kids develop these skills first, which is why a toddler can run around long before they can write their name.

Fine motor skills, on the other hand, are about the small, precise movements. These actions use the little muscles in your hands, fingers, wrists, feet, and toes. Things like writing with a pencil, buttoning a shirt, tying your shoelaces, or using a fork and knife are all examples of fine motor skills. These movements require a lot of control and hand-eye coordination. It’s the reason why building a tiny model airplane is so much harder than kicking a soccer ball. Both types of skills are super important for everyday life.

Who Is the Captain of Your Movement Team?

If your body’s movement system is a team, then the brain is the captain, coach, and manager all rolled into one. But even within the brain, different parts have different jobs. The main area in charge of planning and starting your movements is called the motor cortex. It’s a strip of brain tissue located in the frontal lobe, right near the top of your head.

Think of the motor cortex as the CEO of “You, Inc.” When you decide to do something, like wave to a friend, the idea starts in other parts of your brain. But it’s the motor cortex that creates the actual plan of action. It figures out which muscles need to move, in what order, and with how much force. It then sends those instructions out to the rest of the team. It’s like a master puppeteer pulling all the right strings to make your body move just the way you want.

But the motor cortex doesn’t do it all alone. It gets a lot of help from other brain areas. It receives information from your eyes, ears, and sense of touch to understand what’s happening around you. For example, if you’re reaching for a can on a shelf, your eyes tell the motor cortex how far away it is, so it knows how much to extend your arm. This constant flow of information helps you make smooth, accurate movements instead of just flailing around. This central control unit is as vital as the core of an engine; for example, the design of a stator core lamination is crucial for directing the magnetic fields that make a motor spin correctly.

What Does the “Little Brain” Do?

Tucked away at the back of your head, underneath the main part of your brain, is a structure called the cerebellum. Its name literally means “little brain,” and for a long time, scientists weren’t exactly sure what it did. Now we know it’s one of the most important players on the motor team. If the motor cortex is the CEO who gives the orders, the cerebellum is the expert manager who fine-tunes all the details.

The cerebellum is all about coordination, precision, and timing. When the motor cortex sends out a command to, say, throw a ball, the cerebellum steps in to make sure it’s a good throw. It adjusts the movement based on all the sensory information it’s getting. Is the ball heavy or light? Are you standing on slippery grass? How far do you need to throw it? The cerebellum processes all of this and tweaks the muscle commands to make the movement smooth and accurate. Without your cerebellum, you could still move, but your actions would be clumsy and jerky.

Think about trying to pat your head and rub your tummy at the same time. That tricky coordination is handled by your cerebellum. It’s also essential for learning new motor skills. When you first learn to ride a bike, you’re wobbly and uncoordinated. But with practice, your cerebellum learns the exact sequence of muscle movements needed to stay balanced. Eventually, it becomes automatic, and you don’t even have to think about it. The cerebellum has created a “motor program” for bike riding.

Why Don’t You Fall Over More Often?

Have you ever wondered why you can stand on one leg or walk along a narrow curb without toppling over? You can thank your amazing sense of balance. And just like everything else related to movement, balance is a team effort managed by your brain. It’s a complex skill that relies on information from three main sources.

First, your eyes tell your brain where you are in relation to the objects around you. If you see that you’re leaning too far to one side, you can correct yourself. This is why it’s much harder to balance with your eyes closed! Second, your inner ear has a special system, called the vestibular system, that acts like a tiny level. It can sense gravity and changes in your head’s position, telling your brain if you’re tilting, spinning, or moving forward.

Third, you have tiny sensors in your muscles and joints called proprioceptors. These sensors tell your brain where your body parts are without you having to look. Close your eyes and touch your nose with your finger. How did you know where your nose was? Proprioception! Your brain takes all this information from your eyes, inner ears, and muscles and puts it together. Then, it sends out constant, tiny adjustments to your muscles to keep you upright. It’s a non-stop balancing act that your brain manages perfectly.

How Do We Learn to Ride a Bike or Play Guitar?

Learning a new physical skill can be frustrating at first. Whether it’s learning to ride a bike, play a musical instrument, or master a new dance move, you usually start out feeling clumsy and awkward. This is where the concept of motor learning comes in. Motor learning is the process of your brain creating new pathways and connections to make a new movement automatic.

When you first try a new skill, you have to think about every single step. “Okay, put my left foot here, now move my right hand there.” You’re using the conscious, thinking part of your brain, and it’s slow and inefficient. But every time you practice, you strengthen the neural pathways for that movement. The cerebellum and another brain area called the basal ganglia are heavily involved here. They work to refine the movement, making it smoother, faster, and more accurate with each repetition.

Eventually, after enough practice, the movement becomes a “habit.” It gets stored in your brain as a motor program. This is why an experienced guitarist can play a complex song while talking to someone. They don’t have to think about where their fingers are going; their brain runs the program automatically. This is called muscle memory, but it’s really your brain that’s doing the remembering! It’s an incredible example of how your brain can change and adapt through practice.

What Happens When the Wires Get Crossed?

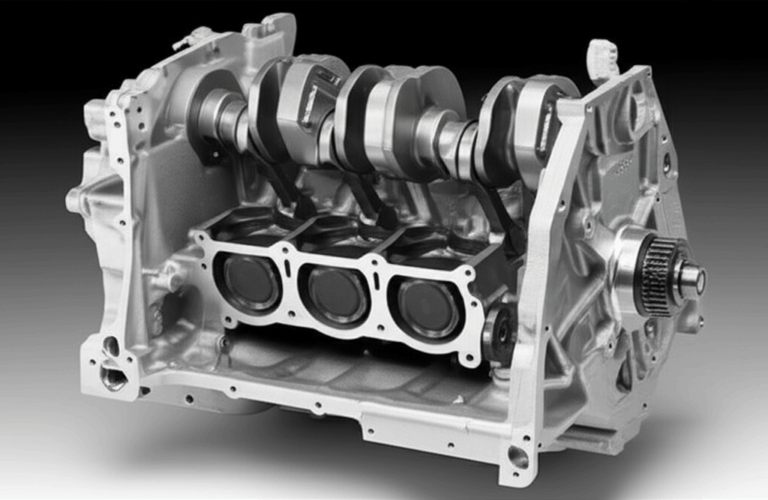

Our motor system is incredibly reliable, but sometimes things can go wrong. Just like a car can have engine trouble, our body’s movement system can experience problems. This can happen for many reasons, such as an injury to the brain or nerves, or certain medical conditions. When the communication between the brain, nerves, and muscles is disrupted, it can lead to motor function problems.

Imagine the nerve pathway from your brain to your hand is like a road. If there’s a roadblock because of an injury, the messages can’t get through properly. This might cause weakness, numbness, or difficulty moving your hand. In other cases, the problem might be in the brain’s control centers. For example, damage to the cerebellum can cause problems with coordination and balance, a condition known as ataxia. People with ataxia might have shaky movements and walk with a wide, unsteady gait.

Problems in another area called the basal ganglia can lead to different kinds of movement issues. Some conditions can cause movements to become slow and stiff, while others can cause extra, involuntary movements like tremors. These issues highlight how perfectly tuned our motor system usually is. Understanding what can go wrong helps us appreciate how much is going right every time we take a step or pick up a pen. This is why understanding the motor principle is so fascinating, as it helps us see the parallels between our own bodies and the machines we build.

Can You Actually Improve Your Motor Skills?

The short answer is a big YES! Your brain is remarkably adaptable, a quality known as neuroplasticity. This means it can change and create new connections throughout your entire life. So, no matter your age, you can always improve your motor skills. The key to improvement is simple but not always easy: practice.

Consistent, focused practice is the best way to get better at any physical activity. When you practice, you’re essentially training your brain. You’re telling it, “This movement is important, so let’s get really good at it.” Your brain responds by strengthening the neural pathways for that specific skill, making the signals travel faster and more efficiently. This is why a basketball player shoots hundreds of free throws a day or a musician plays scales over and over. They are building and reinforcing those motor programs.

It’s also important to challenge yourself. If you’re learning to juggle, once you can comfortably juggle two balls, it’s time to add a third. This pushes your brain to adapt and learn a more complex pattern. Physical exercise, in general, is also fantastic for your motor system. Activities like yoga, dancing, and swimming can improve your balance, coordination, and body awareness, which helps with all other motor skills. So, if there’s a skill you want to learn, don’t be discouraged if you’re not good at it right away. Your brain is ready to learn; you just have to give it the practice it needs.

How Is Your Body Like an Electric Motor?

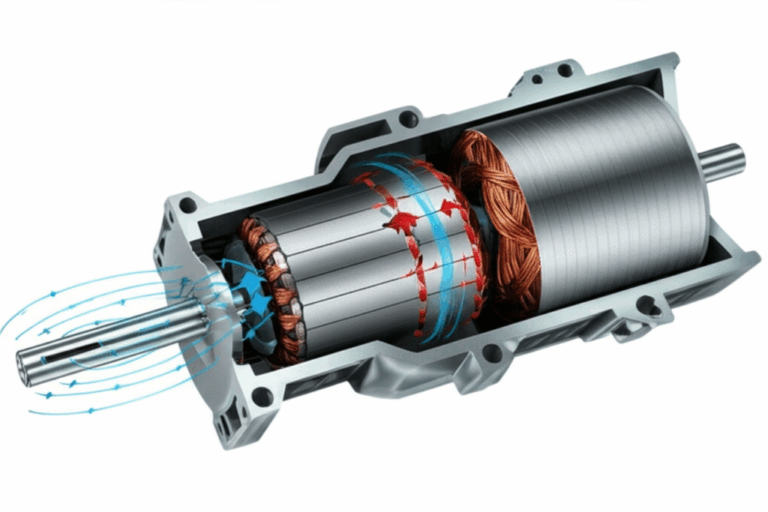

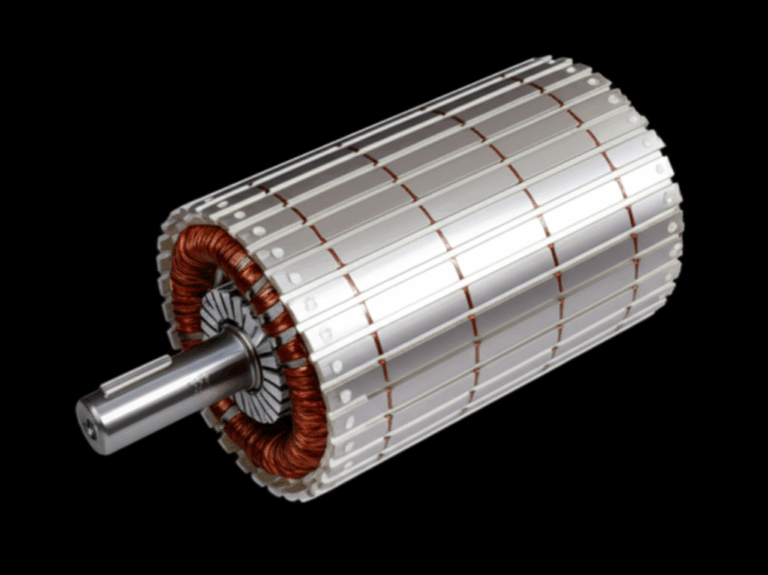

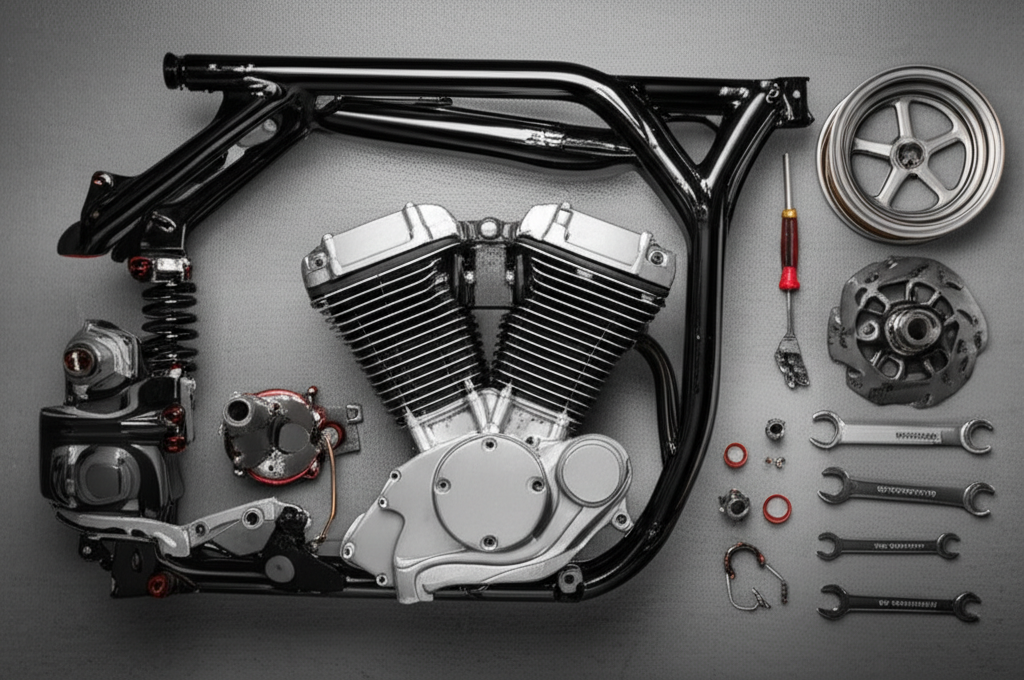

It might sound strange, but there are some cool similarities between your body’s motor system and an electric motor. Both are designed to create movement in a very controlled way. An electric motor uses electricity to create a magnetic field, which causes a central part, the rotor, to spin. Your body uses electrical signals from your nerves to cause your muscles to contract, which makes your limbs move.

In an electric motor, you have a stationary part (the stator) and a rotating part (the rotor). The interaction between them creates motion. You can think of your skeleton as the frame, or stator, and your muscles and limbs as the moving parts. The precision of these parts is key. For example, high-quality motor core laminations are essential for a motor to run efficiently and without wasting energy. Similarly, your brain must precisely control your muscles for efficient, graceful movement. If the signals are sloppy, the movement is clumsy and wastes energy.

Furthermore, some advanced motors, like brushless DC motors, require very specific electrical signals to turn smoothly and powerfully. This is similar to how your brain sends incredibly complex patterns of signals to your muscles to perform a skill like playing the violin. The better the components, like a well-made bldc stator core, the more precise the motor’s control. In the same way, the more you practice a skill, the more precise and efficient your brain’s control becomes. It’s a neat way to think about how principles of engineering and biology can overlap to solve the problem of movement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Motor Function

Q1: Why are babies so clumsy?

Babies are born with some basic reflexes, but their motor system is still under construction! Their cerebellum and motor cortex are not fully developed, and the connections between their brain and muscles are still forming. It takes time and a lot of practice (like rolling over, crawling, and eventually walking) for them to gain control over their bodies.

Q2: Does being “right-handed” or “left-handed” come from the brain?

Yes, it does. For most right-handed people, the left side of the brain is dominant for controlling fine motor skills like writing. For left-handed people, it’s typically the right side of the brain. This is called cerebral dominance.

Q3: Can playing video games improve my motor skills?

Actually, yes! Studies have shown that playing action video games can improve hand-eye coordination, reaction time, and the ability to track multiple objects at once. The quick and precise movements required for many games can be great practice for your fine motor skills.

Q4: What’s the difference between a reflex and a regular movement?

A regular movement, like picking up a book, is voluntary. You decide to do it, and the message starts in your brain. A reflex, like pulling your hand away from a hot stove, is involuntary and much faster. The message for a reflex often travels only to the spinal cord and back to the muscle, bypassing the brain for a quicker response time. Your brain finds out what happened after you’ve already moved!

Key Takeaways to Remember

Thinking about how you move can be a bit overwhelming. There’s a lot going on behind the scenes! But if you remember just a few key things, you’ll have a great grasp of how it all works.

- Motor function is your body’s ability to move, controlled by your brain and nervous system.

- It’s divided into gross motor skills (big movements like running) and fine motor skills (small movements like writing).

- Your brain is the command center, with the motor cortex planning movements and the cerebellum coordinating them.

- Your sense of balance comes from your eyes, inner ears, and sensors in your muscles all working together.

- You can improve any motor skill with practice, which strengthens the pathways in your brain.

- Your body’s movement system shares principles with engineered systems, like electric motors, which also rely on precise control and core components like core lamination stacks.